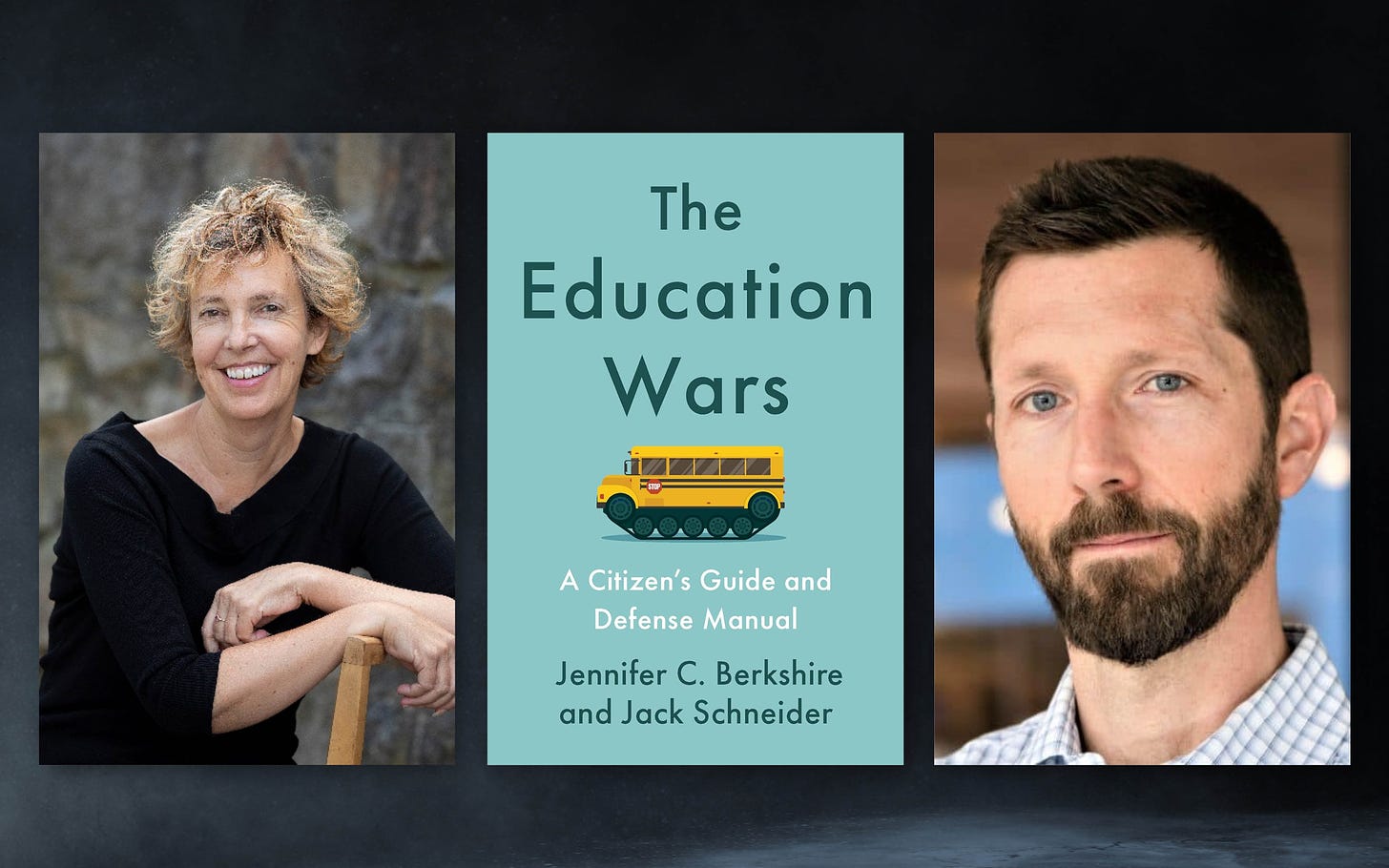

Interview: Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider on their New Book 'The Education Wars: A Citizen’s Guide and Defense Manual'

Learn about the history of the "forever war" against public education, the oligarchs and right-wing and Christian soldiers looking to destroy it, and what you can do to defend it!

Jennifer Berkshire writes about the intersection of education and politics for the Nation, the New Republic, the New York Times, The Baffler, and other publications.

Jack Schneider is the Dwight W. Allen Distinguished Professor at the UMass Amherst, where he leads the Beyond Test Scores Project. He is an award-winning scholar, and his work broadly explores the influence of history, culture, and rhetoric in education policy.

Both Jennifer and Jack co-host the education policy podcast Have You Heard, and they co-authored A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School which came out in 2020. Well, there’s good news, they have another book coming out in July: The Education Wars: A Citizen’s Guide and Defense Manual, which I was lucky enough to get an advanced copy of. They join me today to talk about this new book and why we must defend public education.

[Also listen on Apple, Spotify, Google, iHeart, and Podbean.]

TRANSCRIPT

So how and why did you start working and writing together? What's the origin story of this partnership that's given readers two amazing books – First, A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School, and then your new book, which comes out next month, The Education Wars: A Citizen's Guide and Defense Manual.

Jennifer: It is really kind of amazing that Jack and I have been now working together for quite a long time because what people probably don't realize is that Jack is actually quite a difficult person. I mean, I don't know how I managed to do it.

Jack: I was going to say we met at Professor Xavier's school for talented young people, but clearly Jennifer misremembers this.

Jennifer: So we started working together because we, this is now a number of years ago, dating back to, I don't know, probably 10 years. And we were both concerned about the direction of education policy in Massachusetts, how narrow it was, how obsessively focused on charter schools it was. Jack was teaching at Holy Cross at the time. And I was the author of an irreverent blog chronicling the excesses of the education reform movement.

And we just, you know, we met and we liked each other. And when I needed a co -host for my podcast, I reached out to him and he leapt at the opportunity.

Jack: I agreed to do 10 episodes with her. If that's leaping, then we have different standards for what a jump is. But here we are, I don't know, the better part of 200 episodes in. And in terms of our work, writing together really emerged naturally from the podcast. And I think what was most surprising to me as somebody who had written several books previously was that whereas on prior projects, I went and got a book contract and then had to learn all about a particular topic, when Jennifer and I decided to write Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door, it actually came to, I think, both of us as a realization, like, wait a minute, the book is already written. It's just, it's in our heads and in the transcripts of prior shows. And so it emerged really naturally from the conversations that we had been having for, at that point, I don't know, six years maybe. And this second book really came out of the first book and additional conversation. We're talking with each other basically every week and learning from each other and learning from our guests. Learning from the things that people are sending us in the mailbag for the podcast. So it really has emerged as a kind of activist intellectual community, which I always think is really cool.

That's fantastic. So why did you decide to follow up A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door with the education wars? Why was this necessary?

Jennifer: I think we both felt a real sense of urgency that in large part because of the conversations that Jack just described.

We were hearing from activists and public education advocates all over the country, you know, hey, we are really under assault here. And, you know, we need help being able to explain to the people in our communities what's going on and how the particular issues that are arising where we live relate to all these larger issues.

So for example, it will come as no surprise to anyone that billionaires are behind a lot of these now high profile and very intense efforts to dismantle public schools. But what many people don't realize is that now there are states that basically have their own billionaires. But if you're outside of a state like Missouri, for example, that particular billionaire is not a household name.

And so in a large part, what we were trying to do was make the big picture argument about what's happening, but articulated in a way that would be really useful to people on the ground. And so when you're in conversation with someone and they ask you, I don't understand what is going on in Bucks County? What is up with all the fighting around the schools?

You can either exhaust yourself by trying to explain it to them, or you can refer them to a zippy new book called The Education Wars.

Jack: Yeah, I'll just add that it also came out of a sense of social responsibility that Jennifer and I do the podcast because we feel like it's making us a bit of difference, maybe even occasionally more than a bit and probably often less than a bit. But it's not a project that has any other real purpose. It is very much about connecting with folks who want to know what's happening in education politics and policy. Our goal with the book was actually to try to expand that audience even further, not just in terms of numbers, but in terms of the kinds of people who presently tune into the podcast. We really want to reach folks who ordinarily vote for Republican candidates for office. Because our concern here is not about swinging particular elections in particular ways. It's about helping people make good decisions that actually align with their values in terms of schooling and education more broadly. And we think that the things that are happening right now in terms of the way that culture war is being used as a tactic for prying people's sympathies away from public schools in order to ultimately dismantle the public education system. That's something that we should all be concerned about. There are 50 million young people in the public schools and their parents and caregivers vote in a variety of different ways, but the vast majority of them are glad that there is a public education system, support it, and feel like their children and the young people in their care are getting a pretty decent education, even while they have their questions about the nation's schools or what's happening in other places. The fact is that most people strongly support public education in general and feel pretty positive about the education that the children who they're responsible for raising are getting in particular.

5 Book Recommendations to Further Shine a Light on Public Education in America

They Came for the Schools: One Town's Fight Over Race and Identity, and the New War for America's Classrooms, by Mike Hixenbaugh

Dark Money and the Politics of School Privatization, by Maurice Cunningham

The Death of Public School: How Conservatives Won the War Over Education in America, by Cara Fitzpatrick

Left Back: A Century of Battles over School Reform, by Diane Ravitch

Whose America?: Culture Wars in the Public Schools, by Jonathan Zimmerman

One of the important things that your book does is provide readers historical context. And you remind them that this war on public education is the country's true forever war. And sadly, I'm not sure if there's any end in sight, at least not anytime soon. Can you briefly talk about when the first shots were fired and some of the proxy battles within the overall landscape of public education over the last hundred years or since its inception?

Jack: Yeah, our fighting over the schools is as old as our schools. So you can go back as far as you want.

And you can go back to before there was a public education system. As long as there are young people who are coming from different households to learn together, there are going to be disagreements about things like the role of religion in their education or the degree to which there should be any connection with outside politics or the values that are closely held by people.

And we see that once public education becomes something that we do as a mass project, right, so beyond particular communities, beyond isolated states, so we're talking now by the mid -19th Century, that's when you get the first fights over the curriculum. You get your first fights over what subjects should be taught, who should have access to particular levels of schooling, whether or not science should be taught and if so, whether it should be taught in alignment with particular doctrinal beliefs, arguments about language, right? So there's one that may seem particularly modern and it's actually quite old. So there were debates about the teaching of German in schools. Ben Franklin, right, this is before the existence of public education, was vehemently opposed to young people learning anything in German because he saw it as anti-American and as undermining the ability of Americans to communicate in a single dominant language. What we identify in the book is a slight shift, right, that these battles over schooling are perpetual. And Jennifer and I aren't particularly troubled by them. They can be disturbing. They can have really tragic consequences. So we don't dismiss them.

But we aren't concerned that those threaten the very existence of public education because for the most part, historically, people who are fighting over the schools have accepted the premise that we are going to, at taxpayer expense, educate every young person who walks through the door. But this fight is different because the culture war, as it is unfolding in the schools, has been paired with an ideological project that is designed to dismantle public education. There is a fundamental belief that we should not be using our tax dollars to educate young people and that not all young people deserve to be educated in the same way. And that in fact, we would all be better off if young people were educated quite differently, either according to the beliefs of their parents or according to their presumed utility. And so that's what really troubles us. And that is the difference that we're so concerned with in this book is that our perpetual fights over schooling, which result in occasional flare ups, that those are being intentionally fanned and that gasoline is actually being poured on those fires in order to advance an ideological end that really doesn't square with what most Americans want.

So you just covered a lot of ground there with some of the fundamental ideological battles within the war on public education, which I think there's one of them is whether it should be viewed as a commodity or a public good. Another is whether public education is a democratic project, small D democratic project. Tell me, what is the problem with viewing public education as a commodity?

Jennifer: I mean, we're kind of seeing it play out in live time right now, which is the more we define it as an individual process and something that benefits only the consumer, the harder it is to defend as an institution. And so, right now we're in the process where states, including Pennsylvania, consider and adapt these sweeping school voucher programs that basically take the idea that schooling is something you consume on an individual basis and translating that into policy. The first phase of that is gonna be having the state pick up the tab for part of a family's private education. But we're convinced and we argue in the book that this is really just a way station, that the ultimate, the long-term goal is to have education consumers pay for it themselves. And so that would, right there is prime evidence of what's wrong with thinking about it this way. Why would we pay as a society for something that only benefits you, the consumer? Think about the way that we conceive of and fund higher education. The burden of paying for it is on the student and his or her family, because we conceive of it as something that, that ultimately benefits just that consumer, that end user. The result has been the explosion of a student loan debt problem, something like a trillion dollars, right? Like who would look at that and think, wow, this is a great way to pay for education. Let's restructure our K -12 system along those same lines.

And so those are a couple of the big reasons, but I know that this is something that Jack has written about and thought about extensively.

Jack: Yeah, it's important to recognize that there are costs and consequences when we think about schooling as a private good, when we approach it from the mentality of the consumer and we think about the value of education as being returned to an individual in the form of social mobility. And those costs and consequences include things like no longer recognizing that we are all stakeholders in public education. And there's a downstream consequence of that, which Jennifer was alluding to, which is that if we're not all benefiting from it, then why are we all paying for it? Right? So there's that way of thinking, but there's also another way of thinking about this that is really important to add. And that's that if we are going to be consumers of education, how well are we going to be able to consume it the way we consume other kinds of commodities? Because education is pretty different from cereal or blue jeans or sandwiches. If I want to try new cereal, I can do so every morning for the next six months with no real consequence.

But if I want my daughter to go to a new school, that's not something we can do on a daily basis. That would be bad for her. It would be probably in violation of the school's policies and practices. And it would undermine her education. So how often are we going to be able to switch? Maybe once a year at most. And even that's going to be really problematic. But how well are we going to be able to determine the fit of a school without actually being in the school?

And here's another way in which we become really vulnerable as consumers. So, you know, if I get marketed to by Levis, right, I do have the ability to try on a pair of jeans before I buy them. I don't have that same ability when it comes to a school. That makes us really vulnerable to marketing. And research suggests not only that marketing can be highly misleading, but also that it can be a terrible drain on school resources. Right between 5 and 10% of school funding ends up being spent on advertising rather than on educating young people. There are even more reasons to be concerned about this, among which and perhaps foremost of which is the concern we should have about equity here. Who's going to get left behind if we're all thinking about only our own children, the children for whom we are parents and guardians, right? Who's going to be left behind is those young people who don't have access to resources and who don't have families who are really savvy and informed and able to game the marketplace for their advantage, even when it comes to basic things like providing transportation, right? So how many choices do you have in a so-called school choice marketplace if your family doesn't have a car to get you there, right?

Suddenly your choices are winnowed down pretty severely and even more so if you live in a sparsely populated rural area and by the way all of that, that's a feature not a bug for people who would like to pull apart America's public education system because then what happens is that a lot of people end up having to get their education online through a microschool through an untrained tutor. This is the uberization of public education. And the end goal here is to get people out of fully funded schools where you know in any community that that school is going to have certain kinds of resources. Now that's not to say that we have equitable education in this country or that we have a totally fair distribution of resources, but it's a heck of a lot better than what we'll be looking at in a privatized system in which we're all fending for ourselves.

I think another, and this is something that you raised, an important kind of thing to emphasize is how unequal education perpetuates economic, political, and social inequality. And I think for some, that's almost the point, right? They wanna maintain these structures of inequality. So for example, in Pennsylvania,

Last year there was a conclusion of an almost like 10 year lawsuit brought by, you know, parents, school districts, for fair funding in Pennsylvania. And, you know, the GOP unsurprisingly argued against fair funding. This is what one of the GOP attorneys said at the trial, which I think was really telling. He said:

What use would someone on the McDonald's career track have for Algebra 1? The question is, in my mind, thorough and efficient to what end? To serve the needs of the Commonwealth? Lest we forget the Commonwealth has many needs. There's a need for retail workers, for people who know how to flip a pizza crust.

And for me, I feel like that just kind of sums up why there is such an opposition and ideological opposition to public education because it is egalitarian. It's about creating equity and leveling the field for everyone.

Jennifer: I'm so glad you raised that because we actually open our book with a quote from a young scholar in Pennsylvania who makes the point that equality does not serve plutocrats well. It never has. And that's why they lobby so hard against it. And a lot of people listening to this will be very aware that a number of the same states that have enacted these sweeping school voucher policies have also rolled back all kinds of restrictions on child labor. And I got really interested in what the overlap is. And what's so fascinating is that if you go back to say the 1920s, when we were really fighting it out over child labor and whether it should be banned and whether children should be required to go to school, you had influential people, industrialists, oligarchs, we would call them, recognize them as being today, saying in a very straightforward way exactly the sentiment that you just expressed with that disturbing quote, which is basically that inequality is our natural state. And so a system like public education that's meant to work against inequality is unnatural. And I think in many ways like that is what's driving somebody like a Jeff Yass or a Betsy DeVos, that they really believe that inequality is our natural state. And there are just, there are some kids who are meant to be on that McDonald's line.

So just to pivot a little bit, you know, we were talking about culture war issues, you know, while plutocrats, right, the oligarchs, the people that are against you know, democracy, and public education as being a pillar of democracy, there's also people who, and you note this in your book, who are very uncomfortable with the pace of social change that's been happening over the last, you know, 100 and more years. What we're seeing is a genuine backlash and whitelash against this social change. Can you talk about some of themain issues that you're finding people are the most uncomfortable with or have been the most uncomfortable with over the past several decades?

Jack: Yeah, I think we can start by talking about the role of religion, right? This is one of the oldest disagreements that we have in American education. In fact, it's the reason why there is a robust private education alternative because Catholics didn't want their children educated in schools that were ostensibly nonreligious, nonpartisan, but which still maintained a kind of Protestant veneer to them, including the reading of the King James Bible. So there have been great efforts to take religion out of schools, and that has done a great deal to quell the fighting over the role of religion, but there are still those who believe that religion and education are inseparable. And for those folks, the idea that young people would be learning things in school that are counter to what they would be learning at home in a faith-informed education, that's really problematic and offensive to them. And I think that the most useful way to think about this is to recognize that if the things that those people want to happen in a public education system can be incorporated, recognized, and valued without undermining the education of the young people whose families don't hold those kinds of beliefs, then there's merit in trying to work through that. But oftentimes that simply can't be done. And again, they have the option to not send their children to public schools. What has changed in recent years is there has been a concerted effort to try to turn that into a reason for opposing the very existence of public education, right? That if public schools won't provide a religious education, then there shouldn't be public schools. That the argument historically was that you would receive a taxpayer -supported education that advances democratic values and interests, and that it would be nonreligious. For the last century, that has been more or less the agreement. Now, there's a different kind of argument being made that that's discrimination, right, That that is discrimination against the folks who want a religiously informed education. And that has been used as a way of trying to make schools a site of culture war and religious conflict. And that has blown all of these fights over religion that historically just led people to opt out of the public education system. That's why about 9% of kids are educated in private schools. A very small percentage of them attend highly selective, elite, very expensive private schools, which refer to themselves as independent schools. But most are in religious schools, students who are not in the public education system. And the effort has been to try to capture all of that energy that previously led people to exit the public education system and to transform it into active resistance against public education itself. So there's a case where we see lots of culture warring happening right now. And again, that's by design, right? It's not that we're disagreeing about something that we historically agreed about. We've always had these kinds of disagreements. It's just that there's an intentional effort to try to use those disagreements to pull out some of the stabilizing beams that support the public education system.

Jennifer: I'd just add one more piece to that because I think a lot of people might not be aware that in this country, public schools are really the site through which we both defend and expand civil rights. And so that has set them up decade after decade for exactly these kinds of conflicts. So you can go back to the aftermath of Brown versus Board and we see these kind of battles playing out about race. In the 70s, it was about feminism and multiculturalism. In the 90s, there were intense battles over gay and lesbian rights. And often what you see are, like the demands for change and more inclusion are being led by students themselves. And then you see them coming up against the forces of backlash. So right now we have this effort to basically further expand civil rights to include the rights of trans students. And think about the level of resistance to that. What something like school vouchers do is they say, you know what, what we're gonna do is we're going to remove kids from the constitutional imperative to defend and expand civil rights. We're gonna move them into schools where there is no push for equality. And so I think in many ways, the kind of civil rights story is the way that you have to understand these perpetual battles, but the real backlash to the push for civil rights is such a key part of that too.

It essentially legalizes discrimination under the rubric of religious freedom. I mean, one thing I'm worried about though, is that, you know, the Christian right is good at the long game and we just saw them overturn Roe v. Wade. I mean, my concern is, they've been building up the infrastructure to kind of dismantle public schools, as you've noted, for the last several decades. And here in Pennsylvania, it's ground zero. We have the PA Family Institute, which is the state chapter of the Family Research Council. Their legal armed independence law center is being invited into multiple school districts across the Commonwealth, sometimes in secret because they're offering pro bono services in order for them to have a direct hand in shaping book policies to bathroom policies to any policies regarding LGBTQ students. Is that something that you two are worried about as well?

Jennifer: There are so many reasons to be worried right now. And I thought you actually presented that in a very sort of understated way.

But there's a reason they're going in in secret: The stuff that they're trying to orchestrate is really unpopular. It's why we don't see citizens of all these states that now have sweeping school voucher programs being able to vote on whether they want them. The legislators, the policymakers, the billionaires, and these kind of influential think tanks and organizations that you just described, they know that these are unpopular and that if they're put on the ballot, they'll be voted down, probably overwhelmingly. The same with the culture war stuff at the school board level. People are shocked when we tell them that something like a third of the Moms for Liberty, 1776-style candidates win their elections. That's because two-thirds of the time voters are saying, no, thank you. I don't want what you're offering in the schools.

And so I actually have a lot of hope and it's why our book ends on a very hopeful note. As we, you know, we see now coalitions, growing coalitions of people coming together across lines of difference and saying no thank you to the sort of vision that you just described – and not just rejecting it, but also articulating a far, you know, broader, more expansive vision of what schools should do. And so yes, people should absolutely be concerned, but this is a huge organizing opportunity that I think could potentially leave our schools stronger. But also I think it has the potential to push back against the most extreme parts of the Republican Party.

Jack: Yeah, I think one important thing to add here is that there is no natural constituency that opposes taxpayer-supported education, right? It tends to be more like Social Security than like a woman's reproductive rights. Now, I wish that weren't the case, right? I'll lay my political cards on the table and say that I think people's rights also ought to be something that we value as much as the sorts of programs where we ourselves are all stakeholders. But from a politically pragmatic perspective, we can recognize that Social Security has been impossible for the far right to dislodge despite their hatred for it, right? Because they view it as a massively expensive entitlement program, as well as a socialist effort at redistribution. And they're not entirely wrong about either of those things. It's just many of the rest of us call it justice.

And the same is true of public education. That's why public education is so loathed by those who believe that we all ought to be fending for ourselves in a free market, that we ought to become untethered from one another, both in terms of our financial obligations and the way that we make decisions, right? Decisions should be made by individuals seeking their own self interest in a free market rather than by groups operating on democratic principles.

However, there are 50 million students who are right now, today, enrolled in public schools. And the vast majority of Americans who themselves got an education in this country attended public schools. That means we are stakeholders in that system. It makes it a lot harder to try to remove that from the American people as opposed to something that is more deeply politicized and for which there is a natural constituency against it. That's not to say that it can't be done. So I share the concerns that Jennifer was articulating and that you yourself articulated in the question. But like Jennifer, I'm hopeful that when the American people are alert to what's going on, and again, there are efforts to do this undercover of not literally undercover of darkness, right, to pass through legislation, you know, at two o 'clock in the morning, so that, you know, they can move through a bill, as we saw in New Hampshire not so long ago, that is tremendously unpopular with constituents. Still, I think that the American people, if alert and aware, and that's a part of our effort in this book, and that's a part of the effort of many grassroots communities who we try to name and mention and lift up in the book, that if the American people are aware, this is not something that they will be in favor of.

No, I agree. I think just the one obstacle that a lot of communities are faced with is the unfortunate hollowing out of local media. And even with communities that still have daily newspapers, they're not necessarily covering all the school board meetings or covering all the districts within their certain locale. And so while at the Bucks County Beacon, we try to cover as much as possible, we're just a we're a scrappy progressive underfunded publication that punches above our weight, but even we can't cover everything, although we're trying to. But one thing that you kind of like brought out of that dark and gloomy picture I was painting of the Christian right’s attempts to kind of reshape public education in Pennsylvania, what was some light, one being the fact that they do hold minoritarian positions, which is why they're doing this in secret, they're not being very transparent about it, or even why some candidates, even though they have been known to be members of Moms for Liberty, would not publicly profess that or even ask local Moms for Liberty groups not to endorse them publicly. And it also, another point that you made is that, you know, there's organizing opportunities, which a lot of communities have answered the call to, which have led to victories over Moms for Liberty or Christian right reactionary anti-public education candidates. I was wondering if you could just maybe highlight one or two of your favorite victories that you covered in the book where communities came together, and maybe what were the strategies and messaging that you found were particularly effective?

Jennifer: One of our very favorite ones took place over the border from us in New Hampshire in a tiny little town called Croydon. And New Hampshire is an interesting place because they are essentially under occupation by a libertarian group called the Free State Project that has been quite effective in winning elections to very small local bodies. And so they had folks on the school board in this town and municipal offices, and they were able to orchestrate a pretty savage budget cut to the local school budget. This is a town that's so small that it only has a K through 5 school. And then everybody else, when you get older, you go to a neighboring town to go to school. And so the cut to the budget was so severe that essentially kids going to the local school was gonna be replaced with a micro school where they would be taught online. And instead of a certified teacher, there would just be a guide who sort of hovered around making sure that nobody, you know, like poked an eye out, et cetera. And people who sent their kids to neighboring schools for middle and high school were now going to be forced to shoulder the burden of paying for much of that themselves. And so if you were a family that had a lot of kids, you were suddenly looking at, you know, like having to come up with $20 ,000 a year.

This became a major local organizing effort.

And what was so impressive was not just that they won so handily and I got to be there for the climactic vote when they overturned the original budget cut, but also that they were able to bring together folks across party lines. And so one of the prime organizers who led this campaign had an absolutely enormous Trump sign on her barn. This is a very rural area.

And so I think, you know, what was so inspiring about that was watching people kind of relearn how to talk about education as a public good and ask themselves what kind of a community do we want to be? Now that battle isn't over. There are all sorts of issues in New Hampshire about the way that schools are funded, just like in Pennsylvania, but we really saw there just a dynamic organizing campaign that brings people together can look like.

Jack: We did a recent episode of our podcast where we focused on efforts in rural Idaho to defend public education. And I think there's another uplifting story about folks who are not, you know, deep blue progressives who believe in redistribution and in racial equity. These are folks for whom public education means being able to send their kids to a school rather than sticking them online, for whom having a school in their community means having a place where they can have a center of culture, where they can come together and watch sports and go to the art exhibit of student art and a place to vote. And it just so happens that public schools are often the largest employers in some of these sparsely populated places. We also have talked with organizers in lots of different places, and it's worth calling out the role of religious people here, since we've talked about the role that religion has played in the minds of those seeking to undermine public education. It's then worth calling out Pastors for Texas Children. You know, there you've got a group of faith leaders who see the importance of public education for sustaining our democracy. And for them, the real organizing idea is that the opportunities that we provide for young people are the most important thing that we do as a society.

And so I think there are some really clear galvanizing messages here in terms of defending and preserving public education. And like Jennifer, I tend to be pretty optimistic in terms of what the outcome is if we are forced to really clearly articulate what we get from a public education system and what we want from it. Because one of our great national pastimes in this country is taking our public schools for granted. And in fact, maligning them. If you asked me, you know, make a list of things you wish your daughter's school did better. You'd have to give me a couple hours to complete it. I've got plenty of complaints, and that's because I care so much about it, and she spends so much time there. But if you ask me to do the opposite, and that's something we rarely ask of ourselves or others, write down the things that you really care about and really value. And while you're crafting your list of complaints, think about the things that we could do to address those complaints. I can do that too, and I think we all can. And if we can then focus on things like the role that public education plays in strengthening our communities, in building bonds across groups that may otherwise have nothing to do with each other in our society, in advancing and creating some shared purposes in enabling young people to see each other as equals and to recognize the humanity in one another. I think that that's a pretty inspiring vision and then might be enough for us to take seriously some of the bigger political challenges. Like, okay, well, what's it gonna take to ensure that every school has the resources that it needs to succeed? And how serious are we about things like racial and economic integration so that young people really do go to school with each other and learn to see their fellow Americans as dignified coequals in a democratic society.

And finally, what are your plans this summer when the book comes out in about three weeks? How will you be promoting it?

Jennifer: Well, you know, it's pretty typical for people to do a book tour where they go to a bookstore and they speak to what is often a very small audience. And we're going to do something a little different. We're really treating it as an organizing campaign. And so the groups that we'll be talking to, they could be a parent group, they could be groups of school leaders, teachers, and we will be trying to convince them to join forces with the broadest possible coalition in order to make the case for public schools. So if we had concert t -shirts made, the list down the back will be full of names like Des Moines, Iowa, Madison, Wisconsin, remote New Hampshire and hopefully we'll be coming to a place near you.

And if communities wanted to invite you, how would they go about doing that?

Jennifer: We have a great website for our book. It's Education Wars Book, and there is a little form they can fill out. We'll get right back to you. And we're hoping to visit as many communities as possible.

Jennifer, Jack, thank you so much for your time, your tireless work in defense of public education and for writing this new book, which I hope that everyone will pre-order now from their local bookstores. So thanks again for coming on the Signal.

Jack: It was great to be here.

Jennifer: Thanks for having us.